The construction and demolition (C&D) industry is the largest contributor to U.S. landfills, adding nearly 600 million tons of waste every year—most of it attributable to building demolition. With many sources indicating that our landfills will run out of space in the next 15 years, the urgency of adopting circular construction practices has never been greater. Circular construction aims to keep resources in use for as long as possible by recovering and regenerating products and materials. As architects, we have an imperative to pursue responsible resource management and divert material from the waste stream wherever possible. One way we can do this is through building and material reuse.

Goody Clancy is currently incorporating material salvage in renovations on several college campuses, from which we’ve learned some fundamental lessons about how to design things out of buildings as thoughtfully as we design what goes into them.

Our salvage plan at the ATC building (UMass Amherst, Mt. Ida Campus) proves that material repurposing can be implemented even quite late in a project’s timeline. On this project, salvage work started while construction documents were already well underway. The complete renovation of this c.1998 building sought to create a modern, healthy campus workspace. In its existing condition, the entire building perimeter was taken up by offices, resulting in a dark, lifeless core. By adding glazed office doors—a simple swap for the existing solid wood doors—we were able to bring natural light and views into the center of the space. We were then able to successfully reuse the existing solid doors for bathrooms and “back-of-house” spaces—places where transparency was not helpful.

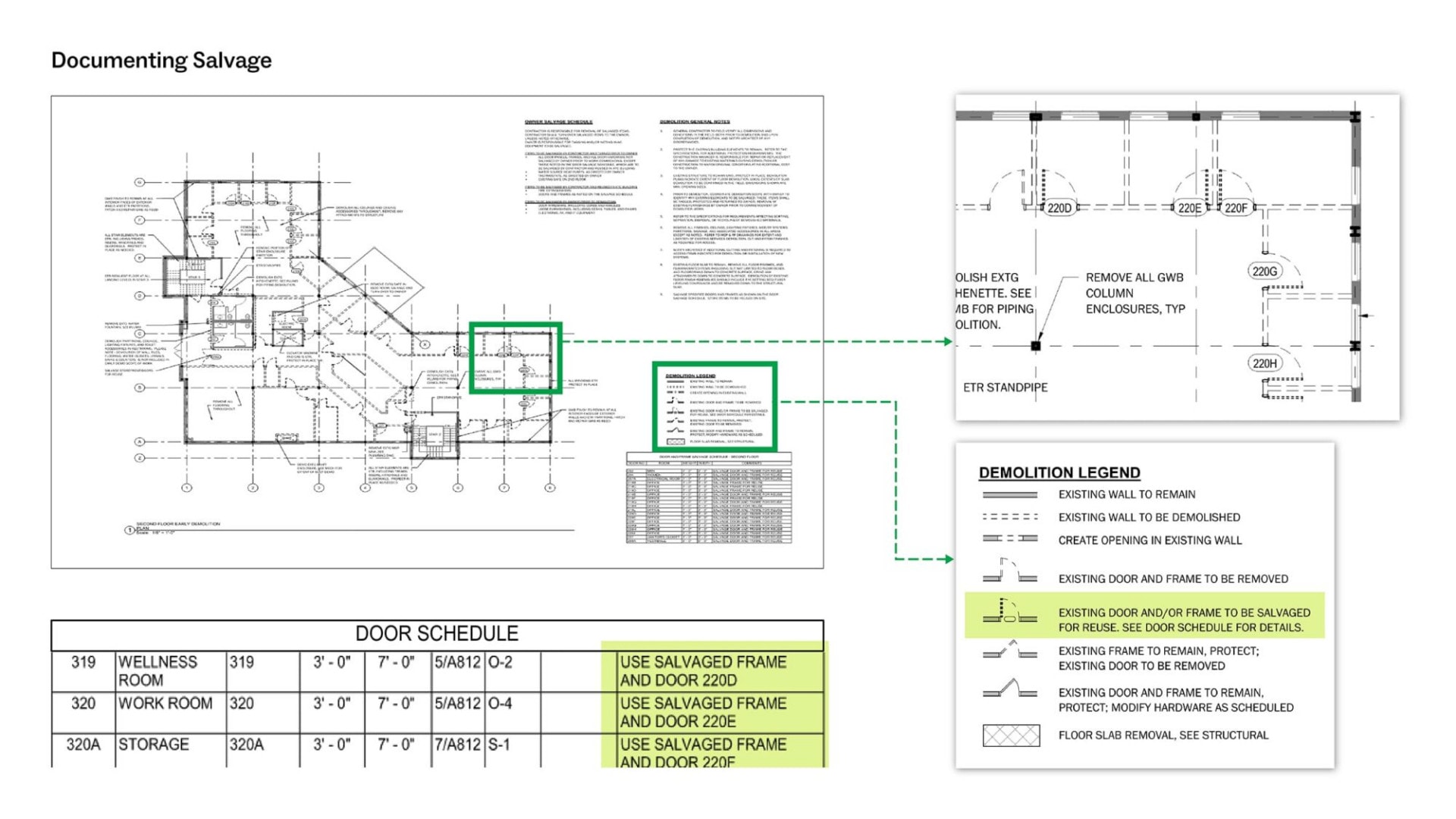

We learned a few basic lessons through this repurposing effort. One lesson-learned was about material surveying and tracking. Each available door and frame was assessed for condition, handedness, and hardware. Although we had already completed most of our construction documents, we were able to include salvaged doors with three simple steps:

- We created a Salvage Schedule—a list of what to recover, by who, and where it would go.

- A graphic label on the demolition drawings clearly identified doors for reuse for a smooth handoff between our demo and renovation teams, who were under separate contracts.

- The door labels reappeared in our renovation door schedule, matching each salvaged door to its new home.

In our renovation of Balch Hall (Cornell), we have been exploring material salvage and repurpose in a very different setting: a historic campus residence hall seven times the size of the ATC building. We were eager to reuse as many of the c.1929 collegiate gothic building’s characterful materials as possible. When code or program requirements made this impossible, we were able to donate usable furniture, fixtures, and other materials through the Ithaca-area’s active salvage community, CR0WD; 17 tons were donated in total.

Our most abundant material was, again, doors: hundreds of bedrooms, each with a hallway door and multiple closet doors—roughly 1,100 solid hardwood doors in total, and all of them incompatible with modern code. We decided to repurpose these doors as wood paneling in common areas. This posed two immediate design questions: what to do with the door hardware, and how to provide for modern electrical requirements. We decided that, in most cases, retaining doorknobs would not only add to the character of the material, it would also give residents a useful place to hang coats and bags. Detailing the doors-as-paneling required additional creativity to accommodate accessible wall outlets and monitor installs.

A delightful part of this project has been designing the reuse of doors from rooms occupied by Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg when she lived in Balch Hall. In partnership with Cornell, we are creating two commemorative installations using these doors together with images of her iconic “dissent collars.” Through this salvage installation, students living in Balch Hall will engage with the history of their place in a unique and beautiful way.

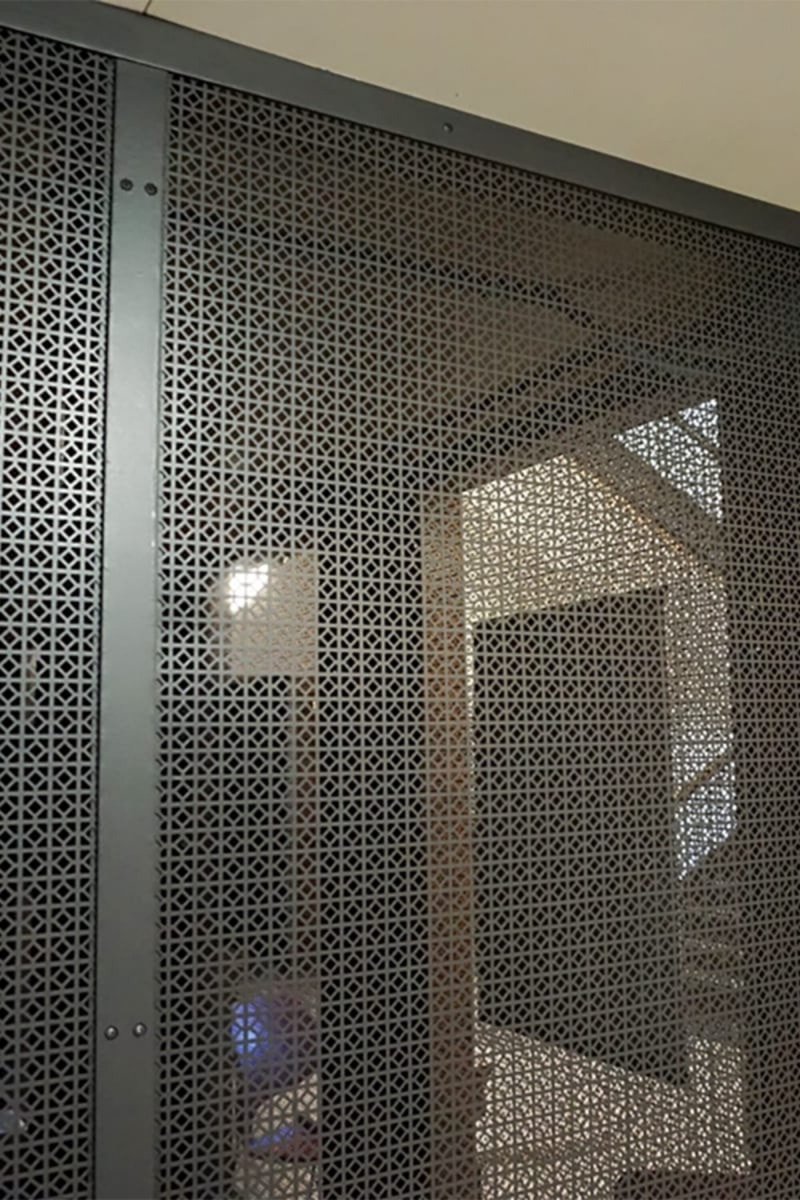

At Goodell Hall (UMass Amherst), material reuse inspired our design from the outset of the project. Constructed in 1934 as a library, the building’s entrance brings visitors into a colonnaded mezzanine of library stacks. The stacks are now being removed to make way for new student services programs, but their perforated metal enclosures—a unique, textural veil—gave our team pause. The design team decided to explore their reuse, eventually deciding to clad a prominent internal volume with the panels, keeping them front and center—revived and reconfigured—as an echo of the building’s origins.

On-site salvage doesn’t guarantee material consistency the way working with new materials does, so it is important to reduce risk wherever possible. One way we reduced risk on this project was to take an alternate design through design development—one that used standard construction materials instead of salvaged metal panels. This ensured that we would not lose time if we were unable to salvage sufficient panels for our needs. We also reduced risk by explicitly identifying the hand-offs between trades, from selective demo to metal fabrications, to the carpentry installer. While this project is still in construction, its reuse story has already inspired our continued exploration of how early identification of salvage opportunities can lead to unique design solutions.

The journey towards circular construction is ongoing, and our work in material salvage and reuse in campus buildings will continue to evolve. We are excited about this work; it not only helps to achieve embodied carbon reduction goals, but it can also help our clients retain elements of their culture and history and reimagine them in ways that contribute to their campus’s unique sense of place.