Out-of-the-Box Programming: Jenga at MIT for Equity and Flexibility

Great projects are driven by the narrative of their future users, the often cacophonic voices of memory, expectations, and fears. For this reason, I have always believed that programming and design must be intimately intertwined – that effective programming provides the foundation for the most successful design.

Engaging stakeholders in the early phases of a project is crucial to success – and something of an art form, crafted anew for each project and client. The range is wide: from diligent data gathering to boardgames and mock-ups, to the palette widening that’s possible with virtual asynchronous tools like Miro boards and surveys. But nothing is more potent than in-person work sessions with use of the right tools to set the imagination free and make input measurable and actionable.

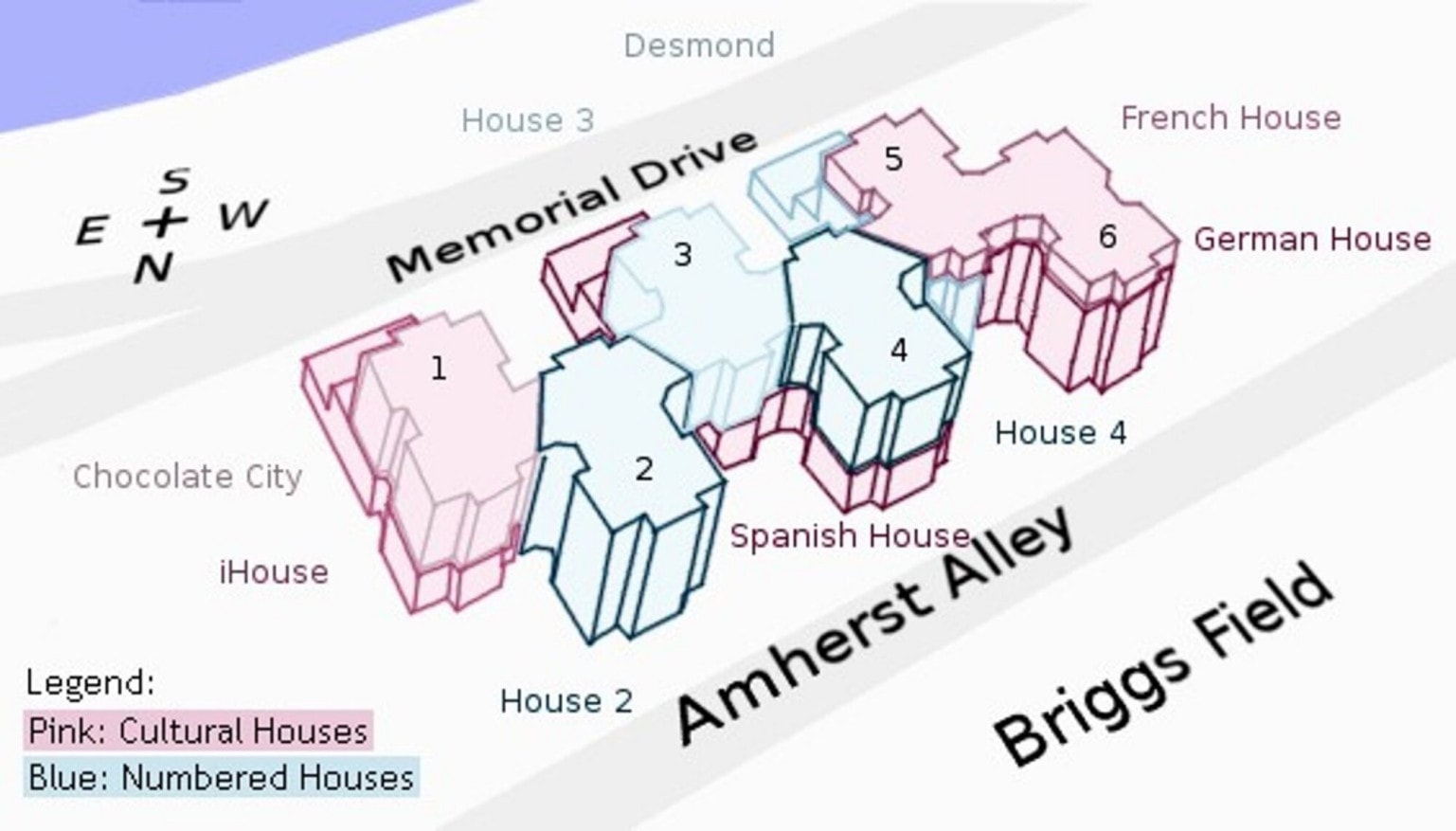

The renovation of New House at MIT posed a unique and delightful challenge: to find a home for nine cook-for-yourself affinity groups each with a strong identity while renovating the 50-year-old building top-to-bottom for accessibility, safety, and comfort. The groups – like Greek housing – have their decades-long history, unique traditions and intellectual focus, and disparate and fluctuating sizes. The design challenge was framed by the relatively inflexible organization of the existing building designed by Josep Lluís Sert in the 1970s: six paired towers with no interconnectivity, each with five levels; three of the six towers projecting towards the river with covetable views of Boston across the Charles River.

Originally, the building housed six affinity groups, each in a tower, with their own social space (kitchen, lounge) located at the first floor, lining a first-floor spine lovingly known as the ‘Arcade’ – like beads on a necklace, flipflopping north and south, alternately oriented towards the river and Amherst Alley and shaping various courtyards. Over time, the number of communities grew, social spaces bubbled up to the upper levels to be more immediate to their users and to take advantage of the spectacular views. The affinity groups intertwined in a spatial dance, like a colorful maze where boundaries shift and melt with every passing semester. But the overall experience for students was disorienting. The building’s physical inflexibility was confounding its social structure and sense of community. Mysterious doors opened between floors, towers, and communities, and it took new residents too much time and energy time to learn to successfully navigate their new home.

The challenge of a wholesale renovation began with how to respect the strong bones of an important building while making every group feel both special and equal, and simultaneously accounting for the battle of feuding numbers and fluctuating group sizes. We knew we were to interlink the towers for universal accessibility, and this simple design move opened new horizons for how to think about the future organization of the building.

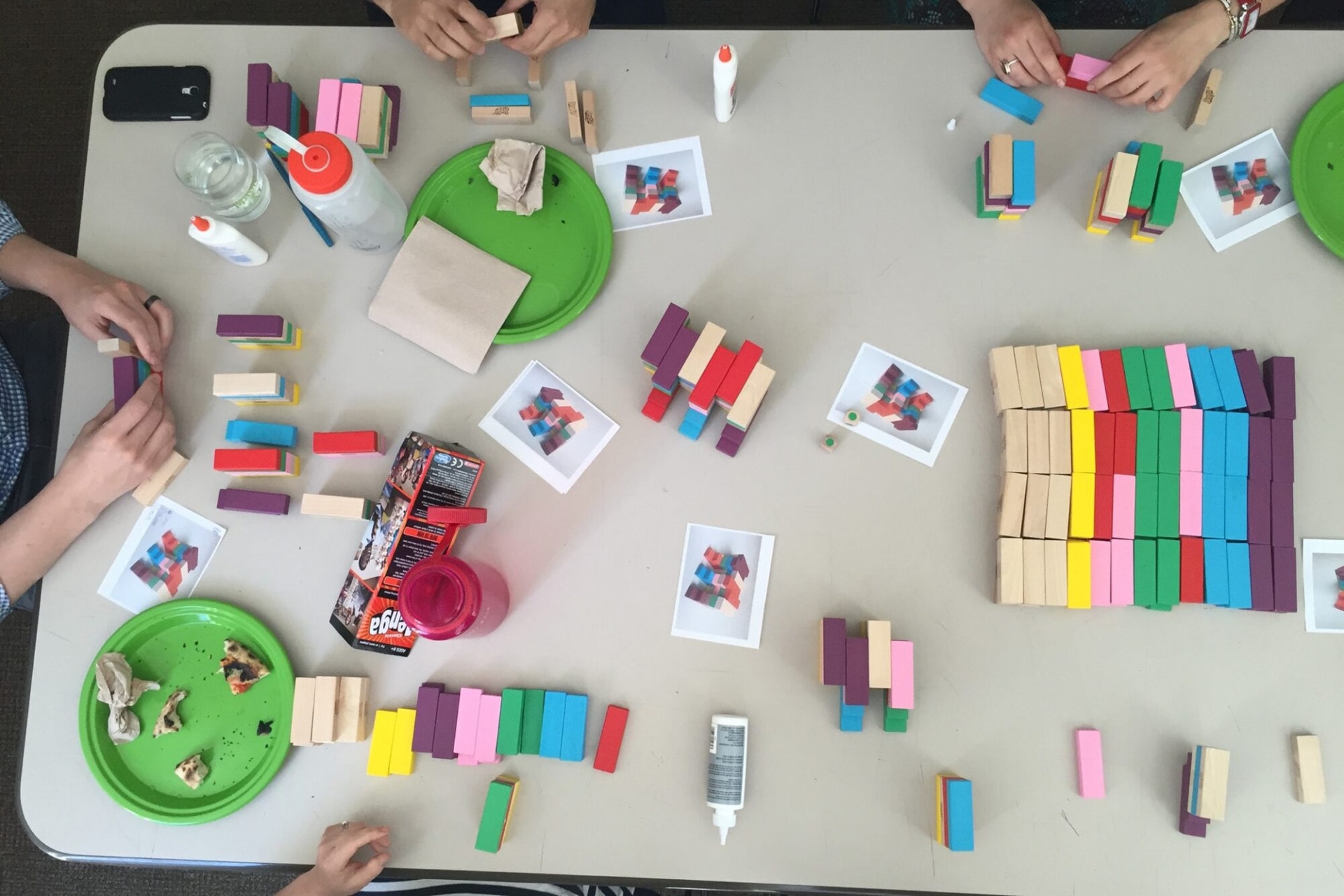

MIT offered us the opportunity to closely collaborate with a group of New House students: a dozen or so residents who knew the community inside out and were given academic credit for their collaboration. From our very first working session with the students, we realized that they had been given front row and significant autonomy in guiding and informing our conversation about the organization and design of the future building. Representatives of MIT and Student Housing confidently sat back and let conversations unfold without intervening.

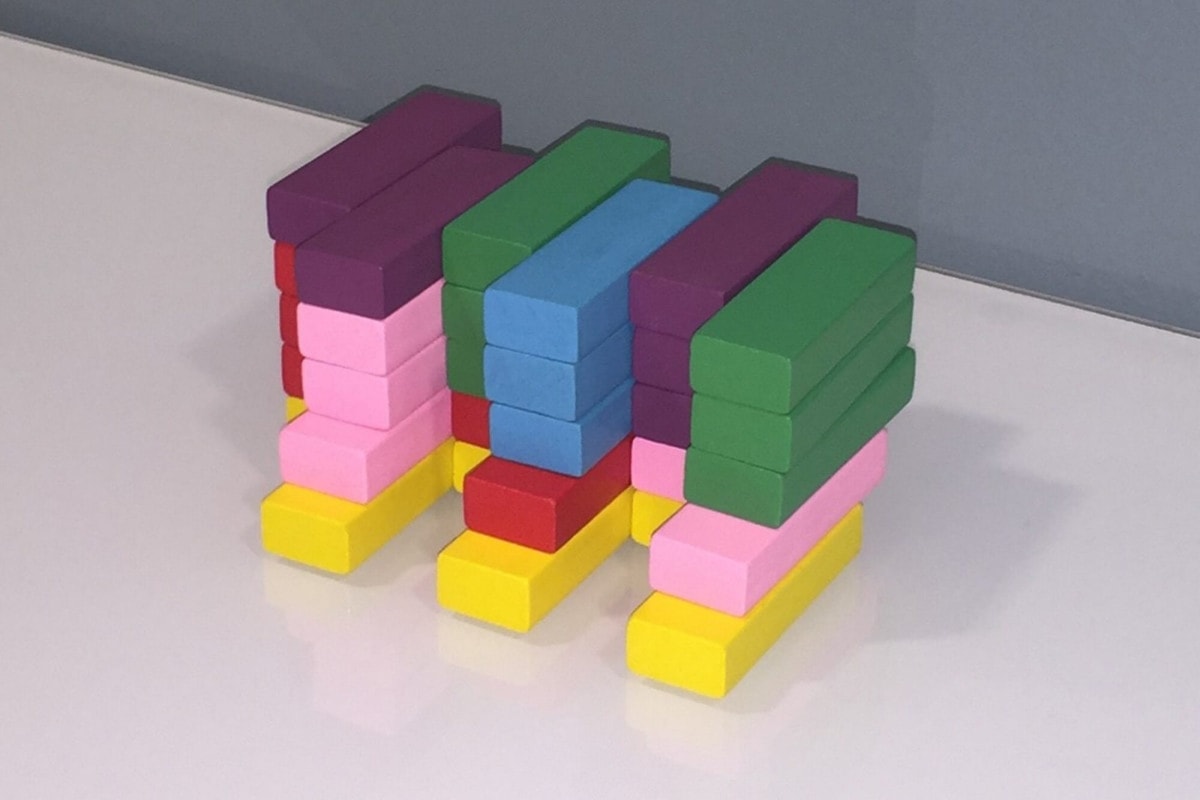

To tackle the programming complexities of this fluid spatial Tetris Game of six towers with five floors and nine groups, we introduced a simple modeling tool: colored Jenga blocks, each color representing an affinity group. (If you’re wondering: colored Jenga is available as a drinking game from Amazon; a happy surprise for the design group!). For a building of five floors and six towers, our toolkit comprised thirty blocks, each representing an average of ten or so residents.

With the help of these blocks, the students and the design team could quickly model various ways of stacking the affinity groups in the building. Should the groups be organized vertically, better resembling the original and current organization, or horizontally, for easier access and sense of place? Or perhaps an L-shaped zone, where some residents are on one floor and a smaller group above or below them, so the effect of blasting music could be contained within the group, a suggestion of one of the students. Should the affinity groups’ lounges alternate north and south, or could we find a way to have all of them face the view? And most importantly, how to design around the fact that some groups were as few as 18 students, the largest over forty?

We played Jenga for an entire design session, producing iteration after iteration of what-ifs, and in the process basic rules emerged.

- Keep all affinity group hubs facing the river for equity and delight.

- Animate the first floor Arcade with program that is shared across the entire building to create community at the building level.

- Affinity group hubs should be located away from the Arcade, with a better sense of intimacy.

- Give each group a second set of shared spaces – quiet areas for study, slightly removed from the hub (but still with views!)

- Flexibility is imperative: for size and horizontal/vertical organization, whatever it takes. We do not know what the future holds.

The last ‘rule’ gave us the most pause. For the next session, we brought more Jenga blocks: this time neutral ones to represent zones of beds between the house hubs that can swing to any hub nearby. Suddenly, a sort of checkerboard pattern emerged, representing nine ‘anchors’ within the building, all facing south, connected by non-designated zones of bedrooms that can be claimed by the groups each semester, allowing for horizontal and vertical expansion, as well as fluidity in size.

The ‘anchors’ consisted of the affinity group hub, proudly projecting towards the river, and an adjacent space, recessed, for the group’s quiet zone and graduate resident tutor. A very simple, and powerful concept, informed by complexity and ingenuity, that makes this building embody a sense of ‘long life loose fit’ – a design attitude that we aim to harness on all renovation (and new) projects to ensure programmatic resilience for our clients.

Now that the renovated building has opened its doors, we are engaging New House students in a post-occupancy evaluation. Recalling the energy and sense of commitment of our original student collaborators, we have not been surprised by the enthusiastic responses to a resident survey. We are thrilled by the resounding appreciation for the natural light, the views, the generosity of shared space, and sense of community and delight that the renovated residence hall is bringing to the students. Over half of the respondents named their own affinity group hub as their favorite space in New House: a powerful testimony to the impact and resolve of the students who pushed us during programming to explore new ways of thinking with them.

Our Jenga block exercise with students provided us with just the right tool to explore the possibilities for the future New House. MIT Housing’s willingness to empower our design team to work with students in this way fostered a unique and successful design conversation aided by unorthodox props.

Cheers to all!